Confession & Prayer

The Sacrament of Confession

Confession is an important and integral aspect of Christian life. Its foundation is Scriptural and its practice goes back to the Apostolic times. The ongoing forgiveness of sins in the Church rests in Him that makes all things possible in the Church: The Holy Spirit sent by Christ from the Father to those who are His.

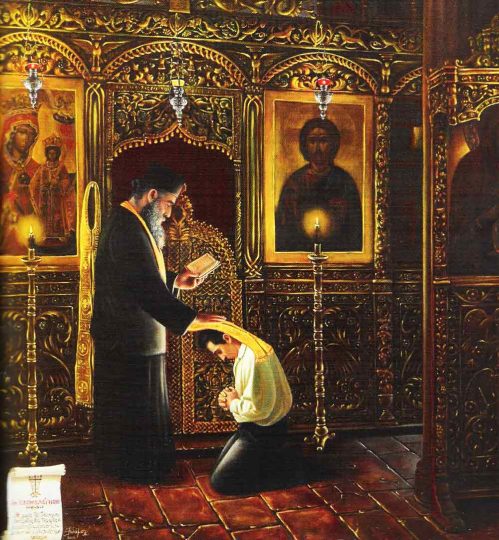

When Jesus sees the Apostles after His resurrection, He breathes on them and says, “Receive the Holy Spirit! If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven. If you retain the sins of any, they are retained.” (John 20:22,23). The presence and the power of Christ’s forgiveness remains in the Church in which all of His gifts reside. Jesus tells His disciples to hear the sins of the people and impart His forgiveness, just like at the Last Supper He tells them to perform what we know as the Eucharist and Holy Communion. Confession was a public part of Christian life in the early Church. In his epistle, James teaches his readers to “confess to one another” (James 5:16). In fact, in the early Christian Church, confession was public. Secret and private confession (at home by oneself) is a modern idea completely unknown in the Bible and throughout Christian history. A Confession which is not made before God, humanity and creation, is no confession at all. If we do not confess our sins in front of God and in front of man as the Church has established, the core of the meaning of this practice is missing: attain humbleness. This is the Orthodox Faith. In the early Church, confession was made to the whole congregation. Afterwards, the priest read a prayer over the person which manifested God’s forgiveness. With time this practice became difficult to keep up because of growth in Church membership. Confession to the whole congregation ceased by the fourth century and the priest came to represent the whole congregation in Confession.

The priest would hear the person’s sins, offer guidance and encouragement, and then pray over the person. This is how confession is still practised today. Confession is totally based on the Bible and the Holy Tradition. Any person who is seriously trying to live an Orthodox Christian life will go to Confession regularly. They will choose a priest with whom they feel comfortable and make time to confess their sins and seek guidance in their spiritual life. The priest is not a judge, but a fatherly friend, a spiritual father. He cannot forgive sins, only God does that, but Christ has given him the authority to hear sins and pray over the person for forgiveness. The priest helps our confessions to be more reflective, less rationalised and more honest, He can act as a mirror for us which feeds back things, we would be more likely to avoid on our own. The priest may guide us into a deeper prayer life and Scripture reading. He slowly becomes what the Orthodox call, our Spiritual Father, nurturing us with the words of Christ, through the power of the Holy Spirit, in our Journey to the Father.

If you haven’t been to confession, then pray for guidance, see a priest and make some time to get together. Ask him how you should prepare and then make the commitment to seek regular confession in a spirit of sincere repentance and faith in God. The rewards to your life will be immense.

Rev. Dimitri Tsakas

Parish Priest of the Parish of St. George – Brisbane (QLD)

(excerpt from Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia)

Mystery of Confession

Why do we confess?

God is the source of all life and joy. Our separation from His life, from the Kingdom of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, inevitably leads us to corruption, despair and death. In coming into this world and becoming one of us, God the Son, Our Lord Jesus Christ, defeats death through His own death and resurrection and offers to all who believe in Him and join themselves to Him the possibility of eternal life.

In the sacrament of Baptism we are mystically, yet really, joined to Christ and to His Living Body – the Church – through the regenerating power of the Holy Spirit working in the baptismal waters. In Christ’s own words ‘…unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God.’ (John 3:5) Unfortunately in our everyday life, even after Baptism, we continue to reject God’s gift of life and His values in so many ways. As we come to terms with this fact and see how often we ‘miss the mark’, we understand that sin still has a hold over us and places a barrier between ourselves and God. ‘If we say that we have no sin,’ writes Saint John, ‘we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us.’ (1 John 1:8)

The sacrament of Confession then becomes for us the means by which we renew the saving work of Baptism in our lives and allows the healing power of God to restore the broken relationship between us and Him caused by our sin. ‘If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness.’ (1 John 1:9)

Why is it important?

All sin disrupts our relationship both with God and with our neighbour. There is no such thing as a ‘private’ sin. Even our innermost thoughts ultimately have an impact on the way we behave and relate to others and God. It was understood by the Church from the earliest times that the only way to reconcile us once again with God and with those whom we have hurt, either directly or indirectly, was to have a public confession of sin. And so St James writes in his epistle: ‘Confess your trespasses to one another.’ (James 5:16) In this way sin is exposed and uprooted and is not allowed to spread either within the life of the individual or the Church, like a spiritual cancer silently eating away at whatever is good and healthy.

In the early Church, confession was made before the whole congregation but over the centuries the priest remained the sole witness of the Church before whom we make our confession to Christ. This maintained the ‘public’ nature of the sacrament, while at the same time preserving the integrity of the act from people who might not show it due respect. The priest then exercises, by the grace of the Holy Spirit, the authority which Christ bestowed on His apostles to proclaim God’s forgiveness on the one who has truly repented and confessed openly. ‘If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.’ (John 20:23)

How to prepare for Confession?

The Sacrament itself is the final act in a process of self-examination and repentance before God. It cannot be done mechanically and without any spiritual preparation for we can only be forgiven for those things which we truly seek to put behind us.

Before we go to Confession, we need to spend some time alone in prayer and reflection so that we can come to terms not only with our actions but with who we are and what we are becoming. In silence we must ask God to reveal to us those things in our life which have become a barrier to our relationship with Him. If it is our first confession, it is a good idea to look over our whole life so far and note down on a piece of paper those major incidents over the years for which we feel guilty or which in some way still occupy our conscience. Then we will look over our more recent life – the last few months, weeks and days – more closely.

As a guide to prompt us, it is good to read the 10 commandments (Exodus 20) and our Lord’s Sermon on the Mount (Matthew chapters 5-7). These passages act as a spiritual mirror in which we can see a reflection of our inner self. As God brings things to mind, we note them down and can then take this ‘list’ with us to confession. In this way we can make sure that we actually say everything we had intended and avoid skipping those sins which may cause us most embarrassment or shame.

What happens at Confession?

Every priest may conduct Confession slightly differently, but generally the priest (wearing an epitrachilion or stole) will say an introductory prayer and then invite us to sit facing an icon of Christ and make our confession. Sometimes the priest may ask questions to prompt us or to clarify a point, but generally we should approach the meeting as we would a visit to the doctor. We come to describe to the priest our sins which are the symptoms of our spiritual disease as honestly and as openly as we can so that he can pray to God for our forgiveness and also advise us as to how to tackle and overcome these sins in everyday life. Our confession therefore has to be clear, without excuses and without discussion of the sins of others. We must trust that God knows all of our circumstances and He will excuse us if need be.

We have to take to Him and ask forgiveness for the inexcusable part which is the sin. At the end of our confession the priest may advise us and sometimes give us an epitimio or penance, which is not a punishment, rather a ‘medicine’ to help eradicate sin from our life. He will then ask us to kneel while he places the epitrachilion over our head and reads the prayer of forgiveness, encouraging us to be confident in God’s mercy and love for us. For every Orthodox Christian, a heartfelt confession is an opportunity to cleanse our inner life and to make a new beginning in our relationship with God – an opportunity to enter once again into the life and joy of God’s Kingdom.

(Excerpts from Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia)

Mystery of Holy Communion

According to Saint Ignatius of Antioch (+ 107 A.D.), Holy Communion is the “Medicine of Immortality”. Our Lord Himself tells us that if we do not eat His Body and drink His Blood, we have no life in us (cf. John 6:53), and He also tells us that “Those who eat My Flesh and drink My Blood abide in Me, and I in them” (John 6:56). Our Lord invites us to be united with Him at every Divine Liturgy by receiving Holy Communion – His Body and Blood.

But, how frequently should we receive Holy Communion? Unfortunately, due to historical circumstances, some have come to believe that receiving Holy Communion a couple of times a year is sufficient. They have forgotten, however, that the reception of Holy Communion is the fulfillment and end-purpose of every Divine Liturgy and that it is the means par excellence of achieving the goal of Orthodox spiritual life – remember, if we do not eat His Body and drink His Blood, we have no life in us (cf. John 6:53). The goal and purpose of the Orthodox Christian life is to be united with the Lord and to become increasingly like Him, little by little by His Grace. Ideally then, we should receive Holy Communion at every Divine Liturgy and, perhaps, even confess before each Liturgy! In practice, however, the Church advises us to receive the Sacraments ‘frequently’ and always under spiritual guidance.

The best way, then, of ascertaining the frequency that we should receive Holy Communion is to simply discuss it with our Father Confessor. The more our strengths and weaknesses are known, the more guidance can be given as to how much ‘medicine’ is required for healing, renewal, and growth.

When children are baptised in the Orthodox Church as infants, and raised in the Church, their parents, grandparents and godparents have just as much responsibility to feed the children’s souls as they have to feed their bodies. One of the most vital sources of this spiritual nourishment is bringing the children to the Divine Liturgy and Holy Communion at least every Sunday. A person does not need to understand how Holy Communion provides nourishment for it to be effective, any more than it is necessary to understand the process of digestion for regular food to be effective. If people do not eat – whether a child or adult – they become weak, malnourished and may die.

Likewise, our souls become weak, withered and may die without spiritual food. Children who attend Divine Liturgy every week since infancy learn at a very early age that receiving Holy Communion is something truly special, and they look forward to it with eager anticipation.

Our Preparation for Holy Communion

It is a truly awesome and an amazing privilege to be united with the Lord by partaking of His Holy Gifts, and so we must not approach casually, frivolously, or without adequate preparation. We prepare ourselves by prayerfully trying to cleanse ourselves of our sins, so that we might be suitable temples for the Lord to dwell in, for He wishes that we will allow Him to make His home in our hearts and bodies. He says to us: “Listen! I am standing at the door, knocking; if you hear my voice and open the door, I will come in to you and eat with you, and you with me” (Revelation 3:20).

We are cleansed by sincere repentance, by Holy Confession, by fasting, by saying the Prayers Before and After Holy Communion (see Central Youth Committee of Victoria – Prayers) and by prayerfully approaching the Holy Gifts, consciously aware that we are partaking of Christ’s Body and Blood and becoming united with Him. The Lord offers us a priceless gift – Himself! This is the best gift in the world – there is nothing better! He asks of us that we be willing to accept His gift of Himself, that He offers to us at His great Banquet Feast, and to properly prepare ourselves to become living temples of His Divine Presence.

Saint Paul cautions us about receiving Holy Communion in an unworthy manner (carelessly or without adequate preparation), saying: “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be answerable for the body and blood of the Lord. Examine yourselves, and only then eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For all who eat and drink without discerning the body, eat and drink judgment against themselves. For this reason many of you are weak and ill, and some have died.” (1 Corinthians 11:27-30).

Again, the best way to prepare for Holy Communion is to always approach according to the specific spiritual guidance given to us by our Father Confessor.

Rev. Chris Dimolianis

Parish Priest of St Efstathios – South Melbourne (VIC)

(Excerpt from Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia)

The Spiritual Father

What is the Role of a Spiritual Father?

This excerpt on how to select a monastery is from a paper on the Orthodox Christian monastic life, yet all they say about the role of the spiritual father, are equally relevant to those who live in the world.

How do you choose a monastery?

The best way is that you choose, or rather, recognize your spiritual father or mother, and he or she will recognize you as his/her spiritual child. If you choose a monastery because the abbot is famous, or the monastery rich and comfortable, or in a favourable location, then your motives are wrong, selfish. “I can only go to a spiritual father who is worthy to receive my repentance” is a statement that comes from outrageous pride and self-opinion.

The spiritual father does not need to be some kind of clairvoyant elder. Rather, he is someone to whom you can open your heart. There is often a mutual recognition, that “this is my father,” and “this is my son.” Or, at least, that this is a person with whom I want to work out my salvation. Monasticism is discipleship. The discipler, the spiritual father or mother, is the one to whom you will promise obedience, as a means of being obedient to Christ. It is a sacramental relationship: obedience given to the spiritual father for Christ’s sake becomes obedience to Christ. The spiritual father will not give you something immoral or illegal—it would be your duty to disobey such a command. Being obedient means cutting off our own will. It is training. But it is also a means of grace, because we are obedient to Christ through our obedience to the spiritual father. This is itself a means of grace, a synergy or cooperation with God, and accomplished by the power of His energy.

We strive to harmonize our will with God’s will, by cutting off our self-will in obedience. Then it becomes all grace, God’s activity within us. But the more we resist, rebel and protest, the more self-willed and independent we are, the more we reject the grace of God. Obedience is not about subjugation. It is not about depriving the disciple of his will, or much less surrender of one’s personhood. These are abuses. Rather, obedience is willing submission in love. The military model of obedience is totally alien to monastic obedience. True monastic obedience, however, requires substantial maturity. But that too is part of the process of growth. The relationship between a spiritual father and son is a relationship of love and respect, mutual in every dimension. It becomes the context in which we authentically develop our personhood, and transcend our ego-centrism. Submission to a spiritual father means to enter into a mutual striving for salvation together (1Peter 5:5). It is a relationship of the most profound intimacy and openness. You come to know each other profoundly. And yet, the relationship of a spiritual father and son is also a participation in Christ’s own sonship to the Father. It is a relationship that is sacramental, full of grace. That grace does not depend on the charismatic gifts of the spiritual father, his maturity or clairvoyance. Of course, he should be someone blessed by the Church to have such a ministry, and likely will be a priest. If the relationship is undertaken in good faith, on both parts, it becomes that sacramental bond in Christ by the Spirit.

It is important to respect and have faith in your spiritual father. But know for certain that your spiritual elder is a sinful man with passions and shortcomings, like yourself. If you have the idea that he is sinless and infallible, you are only setting yourself up for a huge fall. And if you judge your spiritual father for his inevitable failings, you are also setting yourself up for a fall from your own pride and arrogance.

We must remember that this relationship, because it is the very means of working out our salvation, will be tried by fire. Our faith in our spiritual father will be tried by enormous temptations, by his mistakes and shortcomings, and by our own brokenness, rebelliousness and arrogance. But what is important is to persevere through the temptations, and not allow ourself to judge him. It is said that there are very, very few great elders in the world, but what is even more rare is the true disciple. We must remember that our judgment exposes our own hypocrisy, more than anyone else’s.

The parable of the Prodigal Son is one of the Lord’s most vivid illustrations, and used extensively for the monastic life. How profoundly we betray our Father, going off and living prodigally, wasting his riches on harlotry and riotous living. Coming to our self, finally, we repent and return to the Father. How the Father has waited for the return of his beloved son, no matter how much the son’s insensitivity, words and actions have hurt the father. The Father does not assign us a place with the servants, but restores to us our birthright—now a gift of grace. So also does our spiritual father wait for us to repent, to return, so that we may receive the gift of his love.

“Make haste to open to me Thy fatherly embrace, for as the prodigal I have wasted my life. In the unfailing wealth of Thy mercy, O Saviour, reject not my heart in its poverty. For with compunction, I cry to Thee, O Lord: Father, I have sinned against heaven and before Thee” (Troparion at Monastic Tonsure).

You have found your spiritual father when after he gets to know you, you realise that he loves you unconditionally. His is the monastery which you should join.

(Excerpt from Monastery of Saint John of San Francisco)

Prayer Rule

Getting Started

Starting a rule of prayer can be quite intimidating–and keeping one quite discouraging. It helps when we understand that a rule of prayer (in Greek, κανόνας προσευχής) does not mean ‘do this or else’ or ‘follow this rule so you don’t get punished’. Κανόνας here means a measurement, more like a ruler than a rule. So, a rule of prayer is a goal that we strive for each day which we believe, with the guidance of our spiritual father, is actually do-able. We are creatures of habit. Whether we are conscious of it or not we are continually developing either good or bad habits. Developing a habit of daily personal prayer is the best way to counteract the three giants (forgetfulness, laziness, and ignorance) which continuously seek to overcome us. Conversely, we can think of our prayer rule as our ‘tithe’ each day which we offer to the Lord so that He will bless the remainder of it. If even Jesus needed to go off alone and pray to His Father at set intervals, how much more do we need to do this as well?

When should we pray?

This is something particular to each person and their daily schedule, however, the beginning and end of each day seem to work best. The Jews would bring ‘the first fruits’ of the harvest as an offering to the temple so that the Lord would then bless the remainder of their harvest. Similarly, we have the example of those in monastic life who arise at the very early hours of the new day to be alone with God, even before gathering together for common prayer.

By praying when we first wake up (and by making ourselves go to bed at a reasonable hour so that we will get enough rest!) we prioritize our relationship with God over any other relationship or activity. Before the cares of each day rush in we turn to the Lord and surrender it into His capable hands. At the close of each day we can thank Him for all that has come about by His Divine Providence that day; ask His forgiveness for the specific ways in which we strayed from His Holy Will for us, and raise up before Him our concerns and wishes for the morrow.

A spiritual father on the Holy Mountain once told a pilgrim, “If you pray (specifically the Jesus Prayer) for one hour a day, in six months your life will be completely transformed.” Can we each find an hour a day to give the Lord? “I don’t have another hour in my day,” you respond. Let’s look at it this way. The saintly bishop Gerasimos from Holy Cross in Brookline once stated simply, “We can’t give to others what we haven’t first received from God.” In other words, we really can’t afford not to pray either if we want the Lord to bless our interactions throughout each day with others. St. John of Kronstadt even wrote in My Life In Christ that a half an hour of sincere prayer at night is worth three hours of sleep! Still not convinced? Try this. Keep a detailed log of what you do each day for one week. Isn’t quality face-time with God more essential than all those hours of social mediating?

How does this work?

The Lord taught us, “But you, when you pray, go into your room, and when you have shut your door, pray to your Father who is in the secret place; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you openly.” The Fathers of the Church tell us that what is most essential is that our prayer is sincere and from the heart. This doesn’t mean that we do not use prayers that others have written. It simply means that we need to focus our efforts on being real with God.

Prayer starts with the lips, moves to the mind, and then moves on to the heart. When our minds wander (which they do continuously) we gently but firmly bring our attention back to the actual words we are praying. St. John of Kronstadt said for beginners that we should listen for a corresponding “echo” of understanding with each line of a prayer. At some point, when God wills, the prayer of the mind descends into the heart and we are more consciously aware of God’s presence and that He is communicating to us through each word. Then prayers become prayer.

What prayers should we be using?

Most good prayer rules have a combination of five sources: the prayers of the Church, the Psalter, Holy Scripture, noetic (single thought) prayer, and intercessory prayer. We use the prayers of the Church (which are mostly taken from the Divine services) since we are never praying in isolation from the Church even when we are all alone. These prayers, written by saints of the Church whose experience of God is more intimate than our own, act as signposts to safely guide us to approach the fearful throne of God with the right attitude. The psalms are the prayer book of the early Church and express every disposition of man in relation to God.

By reading Holy Scripture, we open up our minds and hearts so the Lord can speak directly to us through the sacred texts. We also read the writings of the Holy Fathers which are all simply insightful and pastoral commentary on Holy Scripture. Noetic or contemplative prayer is the most powerful moment in our rule fulfilling the command to, “Be still and know that I am God.” Having acquired a boldness before God we end our pray rule by raising others up in prayer as their intercessors while asking the intercessions of the saints on our behalf.

What is our goal?

Our goal is to be vanquished by God’s love in prayer. Our goal is to remember to not just say our prayers to get them out of the way but to allow ourselves through prayer to be reacquainted with our Maker and Saviour each day and His immeasurable love for each of us. It is to receive our spiritual hug for the day in the Holy Spirit. We know our prayer rule is working when we don’t want to stop praying; when we feel the peace that comes from having handed our list of things that need to be accomplished that day over to Him. Our goal is to come to the transformative realization that even the thought to pray each day is already the awakening of our soul to the mystical presence of the Lord for He is the one who initiates prayer with us by giving us each day the thought to say our prayers. In the words of St. Gregory of Nyssa, “God is prayer,” because through prayer He takes up His abode in our hearts and rules as our King and our Lord. Come Lord Jesus!

A parish priest for twenty-two years, Fr. Theodore Petrides has served Holy Cross Greek Orthodox Church in Stroudsburg, PA. for the past nineteen. He and Pres. Cristen have six children and two grandchildren (so far). He regularly travels in America as well as Greece (especially the Holy Mountain), Cyprus, and the Holy Land as a pilgrim, guide, and speaker. He has also taken six work groups to Project Mexico since 1999. He is very enthused about the staff and leadership board of OCF!

(Excerpt from Orthodox Christian Fellowship)

The Jesus Prayer

“Throughout your whole life, you cannot find better help than the Jesus Prayer, because this prayer calls and uses the name of Jesus Christ, who gives you His energy. So, when you mention Jesus’ name, you use Jesus as your Own instrument” (Elder Aimilianos of Simonopetra).

The Jesus Prayer is the traditional practice of ceaseless prayer (cf. 1 Thess. 5:17) in the Orthodox Christian Tradition. The standard formula of the Jesus Prayer reads: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me” or, “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, the sinner.” In practice, a variety of forms can be used. The shortest forms are simply “Lord, have mercy” or even more simply “Jesus.”

The Jesus Prayer has a biblical foundation. It is based on the combination of two prayers in the Gospel: that of the blind man in Jericho, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” (Luke 18:38), and that of the tax collector, “God, be merciful to me, the sinner!” (Luke 18:13). The Jesus Prayer is meant to be cultivated ceaselessly, not just during our specified prayer times. We can focus on this prayer while we are doing our ordinary daily tasks of walking, driving, cleaning, cooking, managing children, or anytime, night or day. When this prayer is practiced over time, it can enter into the heart and become what is called “the prayer of the heart.” The immersion into the Holy Name of Jesus, which is a continuation of our baptismal immersion, brings our attention to Christ and Christ, in turn, dwells in us. The prayer warms the heart and becomes an experience of God’s Presence.

Many people have become familiar with the Jesus Prayer through the classic book, “The Way of a Pilgrim”, the story of an anonymous Russian pilgrim who lived in the middle of the nineteenth century. We are told that the pilgrim began by saying the Jesus Prayer a certain number of times every day, increasing from several hundred to several thousand times a day with continuous effort. Then to his surprise, as he tells us, “Early one morning the prayer woke me up as it were.” Ever since then he found the prayer repeating itself constantly in keeping with the rhythm of each heartbeat. It was as though he were carrying a small “murmuring stream” flowing unceasingly in his heart. Prayer in such a person is no longer a series of activities but a permanent state. Bishop Kallistos Ware, however, warns the readers of the Pilgrim against gaining the wrong impression that this journey from strenuous prayer to self- acting prayer is easily attained. The rapid achievement of the pilgrim is something altogether exceptional. More usually, prayer of the heart comes only after a lifetime of ascetic practice.

One of the obstacles in attaining ceaseless prayer is that the human mind is always active. St Theophan the Recluse says that thoughts keep moving restlessly and aimlessly in our mind like the buzzing of flies. It is of little use to say to ourselves “stop thinking” we might as well say “stop breathing.” The rational mind cannot remain completely idle. But while it lies beyond our power to make the continual chattering of the thoughts disappear, what we can do is to detach ourselves from it, gently but persistently. In order to let go the multiplicity of thoughts we must, as Diadochus of Photike recommends, give the mind “some task which will satisfy its need for activity,” that is, something which will keep it sufficiently occupied, without allowing it to be too active. For the same purpose, St Theophan teaches that “to stop the continual jostling of your thoughts you must bind the mind with one thought, or the thought of One [i.e. God] only.” In our case, this one single thought or “the thought of One only” is the holy name of Jesus. The Jesus Prayer is thus a way of keeping guard over the mind and the heart.

Although it uses words, the invocation of the name of Jesus, because of its brevity and simplicity, is capable of leading us beyond the words into the eternal silence of God. The Jesus Prayer is not just a technique devised for leading people into quiet and stillness. According to the biblical tradition, a name stands for the person. The name “Jesus” was announced by an angel to indicate his saving mission (“Jesus” means “he who saves”). During his ministry on earth saving power constantly came forth from his person to heal the sick and deliver the possessed from the dominion of evil spirits. The invocation of the holy name of Jesus has a sacramental effect that renders the Saviour present to us, enabling us to experience his power over the evil spirits.

The idea of “presence” is essential to the Jesus Prayer. However, it deals with a non-iconic or imageless presence of the Lord. St Gregory of Sinai gives this instruction to those who practice the Jesus Prayer: “Keep your intellect free from colours, images and forms.” Our awareness of the presence of Jesus must not be accompanied by any visual concept but must be confined to a simple conviction or feeling. Through the invocation of the name, we are united with Jesus in a direct, unmediated encounter, that is, without any intermediary concept or image. We feel his nearness with our “spiritual senses”, much as we feel the warmth with our bodily senses on entering a heated room.

As long as the prayer remains in the mind, or in the head, it is incomplete. It is necessary to descend from the head to the heart, to “find the place of the heart.” To be more exact, we must descend with the mind to the heart: to “bring down the mind into the heart.” Our aim is “prayer of the mind in the heart.” It is the special power of the Jesus Prayer to accomplish the union of the mind and the heart.

In order to bring the mind into the heart, our heart must first be awakened. As Christians we have received the Holy Spirit at our Baptism and Chrismation. As the Holy Spirit dwells in the sanctuary of our heart and is unceasingly praying in us, we ourselves carry within us a constant prayer. But most of us are unconscious of his presence and the prayer which continuously goes on in us. Our heart lies asleep and needs to be awakened to this inner reality. The Jesus Prayer is a powerful means for awakening our heart, enabling us to become aware of the secret indwelling of the Spirit in a conscious way.

It is important to realise that the essential point of the prayer is not the act of repetition in itself, but the One to whom we speak. The prayer is not simply a rhythmic incantation or ‘mantra’ but an invocation addressed to another person and thus implies a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. The Jesus Prayer exists within a certain context which is, first of all, one of faith and repentance. Removed from this context the prayer loses its meaning. The invocation presupposes our faith in Jesus Christ as our Lord and Saviour. Without this confession of faith there is no Jesus Prayer. Also, repentance implies that we are attempting to live a life “in Christ” and so, aspiring always to be Christ-like.

The aim of the Jesus Prayer, therefore, is not simply the laying aside of all thoughts, but an encounter with Someone. It is not so much prayer emptied of thoughts but prayer filled with the Beloved – our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ.

Rev. Chris Dimolianis

Parish Priest of St Efstathios – South Melbourne (VIC)

(Excerpt from Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia)

Specific Prayers

There are specific prayers for almost everything. For Illness, Meals, Holy Communion, Travel, School, etc.

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia Book of Prayers in English

Vigils

The All-Night Vigil comprises the daily services of Great Vespers, Matins, and First Hour. It is appointed for the evening before each Great Feast and every Sunday (which is, in effect, a Little Pascha). The feasts of certain saints also call for a Vigil. It is called “all-night” because in ancient times in Palestine where it first developed, it began at sunset and continued through the night until dawn. Later, as the service spread through the Church, out of condescension to the weakness of the faithful, it was abbreviated to begin late in the evening (but before midnight) and to last until morning. Now in normal parish use, it is abbreviated still further, beginning earlier in the evening and lasting but two or three hours. In our Monastery, the length varies between feasts.

Our Monastery regularly has vigils. Please refer to Facebook for dates and times.